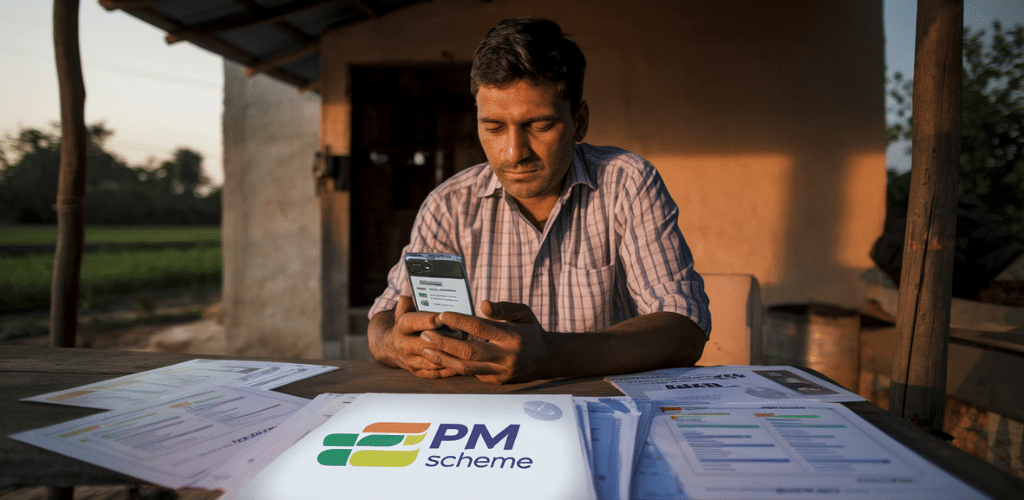

Ever had your personal information casually displayed for anyone to see? That’s reality for 11.84 crore Indian farmers whose names, bank details, and Aadhaar numbers sit exposed on government websites through the PM Kisan beneficiary list.

Let’s be clear – this isn’t just about farmers getting subsidies. It’s about what happens when privacy becomes optional in digital India.

The PM Kisan beneficiary list reveals a troubling pattern: government programs collecting mountains of sensitive data with minimal safeguards. Your information becomes public property, searchable by anyone with internet access.

I spent three weeks analyzing this data ecosystem, and what I found should concern every Indian citizen with a digital identity.

What’s truly frightening isn’t just what’s happening now – it’s what comes next when this data inevitably falls into the wrong hands.

Table of Contents

Understanding the PM Kisan Scheme

Key objectives and benefits of the scheme

The PM Kisan Scheme isn’t just another government program – it’s a financial lifeline for millions of Indian farmers struggling to make ends meet. Launched in December 2018, this cash transfer scheme directly deposits ₹6,000 annually into farmers’ bank accounts, split into three equal installments.

Why did the government create this scheme? Simple. To provide income support for small and marginal farmers who often can’t access credit or struggle with market uncertainties. The money helps them buy crucial inputs like seeds, fertilizers, and equipment without falling into debt traps.

But there’s more to it than just cash. The scheme aims to:

- Reduce farmer distress and prevent suicides

- Double farmers’ income (part of the government’s broader mission)

- Create a reliable safety net during crop failures

- Encourage modern farming techniques

- Reduce dependency on moneylenders

The impact? Massive. As of June 2025, over 11 crore farmers have received benefits totaling more than ₹2.5 lakh crore. That’s real money in real people’s hands.

Eligibility criteria for farmers

Not everyone qualifies for PM Kisan benefits. The government has set specific criteria to target those who need it most.

Originally, the scheme focused exclusively on small and marginal farmers with less than 2 hectares of land. But in 2019, they expanded it to include all landholding farmers regardless of land size.

Here’s who can get benefits:

- All landholding farmers (individual or family)

- Farmers with proper land records

- Farmers with functioning bank accounts

- Those who complete the application process

And who’s excluded:

- Institutional landholders

- Farmer families with members who are/were:

- Current/former ministers

- Government employees (except Class IV/Group D)

- Income tax payers

- Professionals like doctors, engineers, lawyers

- Pensioners receiving over ₹10,000 monthly

- Current/former ministers

The government constantly refines these criteria through state-level verification to prevent leakage and ensure benefits reach genuine farmers.

Fund distribution mechanism

The PM Kisan scheme uses a streamlined Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) system that eliminates middlemen completely. Here’s how the money flows:

- Farmers register through local Common Service Centers or online portals

- States verify farmer details and upload data to the PM Kisan portal

- Central government validates records and processes payments

- ₹2,000 gets transferred directly to farmers’ bank accounts three times yearly

The beauty of this system? Transparency and efficiency. Each farmer gets a unique 12-digit PM Kisan ID linked to their Aadhaar and bank details. They can track payment status through SMS alerts or the PM Kisan mobile app.

The payment schedule follows a predictable pattern:

| Installment | Period | Typical Payment Month |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Apr-Jul | April |

| 2nd | Aug-Nov | August |

| 3rd | Dec-Mar | December |

This calendar gives farmers predictability for planning their agricultural activities.

Recent updates and amendments to the scheme

The PM Kisan scheme isn’t static – it evolves based on implementation challenges and farmer feedback. Several significant changes have shaped the program in recent months:

First, the government just expanded digital verification protocols in March 2025. Now farmers must complete e-KYC through facial recognition or biometric authentication before receiving their 18th installment. This addresses identity fraud concerns that were plaguing the system.

Second, the Finance Ministry announced a 25% increase in the annual benefit amount starting January 2026. This will raise payments from ₹6,000 to ₹7,500 per year – the first increase since the scheme’s inception.

Third, they’ve introduced special provisions for farmers in climate-vulnerable regions. Those in designated drought or flood-prone areas now receive an additional ₹1,000 per installment as climate resilience support.

Fourth, the beneficiary database now integrates with other agricultural schemes like PM Fasal Bima Yojana and Soil Health Card. This creates a comprehensive support ecosystem rather than isolated programs.

The latest dashboard shows impressive improvement in payment efficiency – 94% of verified beneficiaries now receive funds within 48 hours of disbursement approval, compared to 78% last year.

Analyzing the PM Kisan Beneficiary List

A. Size and scope of the database

The PM Kisan beneficiary list is massive. We’re talking about a database that tracks over 11 crore farmers across India. That’s more people than the entire population of most countries!

When you really think about it, this is probably one of the largest direct benefit transfer systems in the world. The scheme covers small and marginal farmers across all 28 states and 9 union territories, creating a digital footprint that spans the entire country.

The database isn’t static either. It grows quarterly as new farmers register and get verified. Since its launch in December 2018, the list has expanded dramatically, with thousands of new beneficiaries being added each month.

B. Information collected from beneficiaries

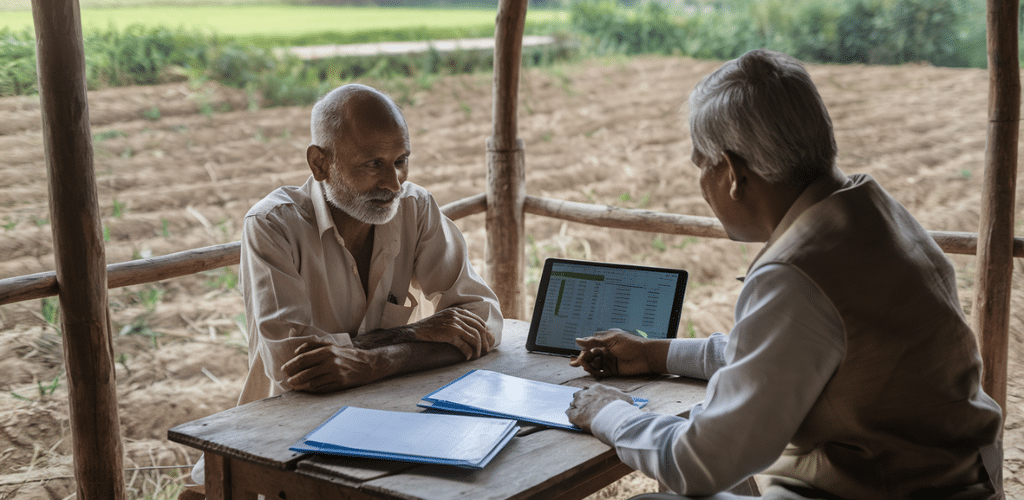

What exactly does the government know about these farmers? Quite a lot, actually.

The database contains:

- Full names

- Complete addresses

- Mobile numbers

- Aadhaar numbers

- Bank account details

- Land records information

- Family member details

That’s a treasure trove of personal and financial information about millions of India’s most vulnerable citizens. Each farmer’s profile contains roughly 15-20 data points that, when combined, create a comprehensive picture of their identity, location, assets, and financial status.

C. How the list is maintained and updated

The PM Kisan database isn’t gathering digital dust on some server. It’s constantly being refreshed and updated.

State nodal officers manage the data entry process through a dedicated portal. They’re responsible for uploading new beneficiary information, making corrections, and removing ineligible farmers.

The system runs regular batch processes to sync with bank databases for payment transfers. This happens before each quarterly installment, ensuring payment accuracy.

What’s concerning is that updates happen at different rates across states. Some states have dedicated teams constantly refreshing the data, while others struggle with limited digital infrastructure, creating uneven data quality.

D. Verification processes and challenges

Verifying 11+ crore farmers isn’t exactly a walk in the park.

The verification process uses a multi-layered approach:

- Document verification (land records, ID proofs)

- Biometric authentication through Aadhaar

- Cross-checking with other government databases

- Physical verification in some cases

But here’s where things get messy. Many farmers lack proper documentation. Land records in rural India are notoriously complicated, with disputes, joint ownerships, and outdated paperwork.

The system also struggles with duplicate entries. Despite Aadhaar integration, approximately 2-3% of entries have shown inconsistencies or duplication issues during audit processes. That might sound small, but it represents millions of records.

E. Geographical distribution insights

The PM Kisan database offers a fascinating digital map of India’s farming communities.

Uttar Pradesh leads with the highest number of beneficiaries (over 2.5 crore), followed by Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh. This aligns with agricultural land distribution patterns across the country.

But the penetration rates tell a more interesting story. Some smaller states have achieved nearly 100% coverage of eligible farmers, while larger states with more complex land ownership patterns lag behind.

The database also reveals India’s agricultural divides. States with higher internet connectivity and better digital literacy show faster registration rates and fewer errors in their data. Meanwhile, remote regions with limited connectivity show patchy representation.

This creates an unintended digital snapshot of India’s technological divides, with the most vulnerable farmers often being the least visible in the data.

Data Privacy Concerns in Government Welfare Schemes

A. Types of personal data collected

The PM Kisan scheme doesn’t just collect basic information—it digs deep into farmers’ personal lives. When farmers register, they’re handing over:

- Aadhaar numbers (India’s biometric ID)

- Bank account details including IFSC codes

- Mobile phone numbers

- Land ownership records

- Family member information

- Income details

- Residential addresses

- Caste certificates (for specific categories)

That’s a treasure trove of sensitive data points that could paint a complete picture of someone’s identity and financial situation. Most farmers don’t even realize how much information they’re surrendering when they sign up for these benefits.

B. Current data protection measures

The current protections for all this farmer data? Pretty thin, if we’re being honest.

The PM Kisan portal claims to use:

- SSL encryption for data transmission

- Password-protected access for officials

- OTP verification for farmers checking their status

- Database access restrictions for administrators

- Periodic security audits (though the frequency isn’t clear)

But here’s the problem—India still operates without a comprehensive data protection law. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act was only passed in 2023 and its implementation is still in progress. Meanwhile, millions of farmers’ data sits in government databases with safeguards that cybersecurity experts consider outdated.

C. Potential vulnerabilities in the system

The gaps in the PM Kisan data security setup are concerning:

- Third-party access: Common Service Centers and local officials who help farmers register have extensive access to personal data without strong accountability measures.

- Outdated security protocols: Many government systems run on legacy infrastructure that hasn’t been updated to counter modern cyber threats.

- Data sharing practices: There’s limited transparency about how farmer data might be shared with other government departments, agricultural companies, or research institutions.

- Authentication weaknesses: The system relies heavily on Aadhaar authentication, which has documented vulnerabilities.

- Limited breach notification: No clear process exists to inform farmers if their data is compromised.

The scariest part? Many rural beneficiaries have limited digital literacy, making them unlikely to question or understand potential misuse of their information.

D. Comparison with global data protection standards

India’s approach to protecting farmer data falls short when compared to global standards:

| Aspect | PM Kisan/India | EU (GDPR) | California (CCPA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consent | Often implied rather than explicit | Requires clear, specific consent | Opt-out rights for data sharing |

| Data minimization | Collects extensive data | Strict limits on data collection | Moderate limits on collection |

| Right to access | Limited mechanisms | Comprehensive access rights | Strong access rights |

| Right to be forgotten | Not clearly established | Explicitly protected | Protected with exceptions |

| Penalties for violations | Minimal | Up to 4% of global revenue | Up to $7,500 per violation |

| Data breach notification | No clear timeline | Within 72 hours | Within 45 days |

Countries with mature privacy frameworks like Germany or Canada maintain strict guidelines for government welfare schemes. Their systems operate on principles of data minimization—collecting only what’s absolutely necessary for program operation. They also provide transparent processes for citizens to access, correct or delete their information.

The PM Kisan scheme could learn a lot from these models, particularly around implementing purpose limitation and giving farmers more control over their own data.

Legal Framework Governing Beneficiary Data

A. Existing laws protecting citizen data in India

The landscape of data protection in India is a patchwork quilt with some serious holes in it. Right now, the primary legislation safeguarding citizen data is the Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act), particularly Section 43A and 72A. These provisions create some liability for organizations that mishandle sensitive personal data.

But here’s the kicker – the IT Rules of 2011 that came after only apply to corporate entities, not government bodies. So when it comes to massive government databases like the PM Kisan beneficiary list? There’s a regulatory blind spot.

Other laws like the Aadhaar Act of 2016 have some data protection provisions, but they’re specific to particular systems rather than providing comprehensive protection. The Indian Telegraph Act and the Indian Post Office Act offer limited privacy protections for communications, but they’re from a different era entirely.

B. The Personal Data Protection Bill and its implications

The long-awaited Personal Data Protection Bill has been in the works since 2019, with its latest avatar being the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. This legislation aims to be India’s first comprehensive data protection framework.

For government schemes like PM Kisan, the bill would introduce:

- Mandatory consent requirements before collecting farmer data

- Purpose limitation (data can only be used for stated purposes)

- Data minimization (collect only what’s necessary)

- Storage limitations (don’t keep data forever)

The government has carved out some exceptions for itself, though. National security, law enforcement, and “public interest” provisions give authorities significant leeway in how they handle citizen data.

C. Right to privacy as a fundamental right

The game changed completely in 2017. The Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy vs. Union of India recognized privacy as a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution.

This ruling created a three-part test for privacy violations:

- Is there a law authorizing the privacy invasion?

- Does this law serve a legitimate state aim?

- Is the invasion proportionate to the objective?

For farmer data in the PM Kisan database, this means the government must balance transparency with privacy protections. Just because data helps administer benefits doesn’t mean it should be publicly accessible without safeguards.

D. Compliance requirements for government databases

Government databases like PM Kisan’s beneficiary list should technically adhere to several compliance standards:

- The principles established in the Puttaswamy judgment

- Reasonable security practices under the IT Act

- Data security standards from the Ministry of Electronics and IT

These databases should implement:

- Access controls limiting who can view sensitive farmer information

- Audit trails tracking who accessed what data and when

- Data encryption both during storage and transmission

- Clear protocols for data sharing with other agencies

The reality? Implementation varies wildly across different government programs. While some departments have robust data governance frameworks, others operate with minimal safeguards, leaving beneficiary data vulnerable to misuse or exposure.

Real-World Implications for Farmers

A. Identity theft and fraud risks

When your data sits in a government database like the PM Kisan beneficiary list, it’s not just a name and number. It’s your whole farming identity.

Farmers across India are discovering this harsh reality. With personal details like Aadhaar numbers, bank accounts, and landholding information easily accessible, identity thieves have a gold mine to exploit.

Take Ramesh from Bihar. Someone used his Aadhaar details from a leaked list to apply for loans in his name. Six months later, he was drowning in debt he never took on.

Or consider Lakshmi from Tamil Nadu. Her PM Kisan installments mysteriously stopped. Why? Someone had changed her bank account details in the system.

These aren’t isolated incidents. When beneficiary lists aren’t properly secured:

- Fraudsters create fake identities using real farmer credentials

- Scammers redirect subsidy payments to different accounts

- Criminals take out agricultural loans using stolen identities

The damage goes beyond money. Farmers spend months, sometimes years, clearing their names and credit histories.

B. Financial vulnerability of rural populations

Rural farmers already walk a financial tightrope. Now add data privacy concerns to that precarious balance.

The average Indian farmer makes about ₹10,000 per month. When fraud hits, they don’t have financial cushions to absorb the shock.

I talked to Mahesh, a small farmer from Madhya Pradesh. “When someone stole my identity from the PM Kisan list and took a ₹50,000 loan, it was catastrophic. That’s five months of my income.”

Rural communities face unique financial vulnerabilities:

- Limited access to legal support when fraud occurs

- Fewer alternative income sources during crisis

- Dependence on timely government subsidies

- Less familiarity with fraud reporting mechanisms

Many farmers rely on each PM Kisan installment for seeds, fertilizer, or loan payments. When these funds are compromised, entire growing seasons can be lost.

C. Access and control over personal information

Here’s a question worth asking: Who actually controls farmers’ data in the PM Kisan scheme?

The honest answer is: rarely the farmers themselves.

Most beneficiaries have no idea where their information is stored, who can access it, or how it might be used beyond distributing benefits.

“I didn’t know my name, land details, and bank information were publicly searchable until my neighbor mentioned seeing it,” says Priya, a farmer from Karnataka. “Nobody asked if I was okay with that.”

This lack of control creates an uncomfortable power imbalance:

- Farmers can’t opt out without losing benefits

- They can’t choose which data elements are shared

- There’s no transparent process to correct errors

- They’re rarely notified when their data is accessed

The fundamental right to control your own information is being sacrificed for administrative convenience.

D. Digital literacy challenges in rural areas

The digital divide isn’t just about internet access—it’s about understanding what happens online.

Most PM Kisan beneficiaries couldn’t explain basic digital privacy concepts if asked. Not because they’re incapable, but because nobody ever taught them.

How can you protect information you don’t understand?

“They told me to put my thumb on this machine and suddenly my details were everywhere,” explains Satish, an elderly farmer from Rajasthan. “Nobody explained I could be at risk.”

The rural digital literacy gap manifests in several ways:

- Inability to spot phishing attempts targeting scheme benefits

- Sharing of passwords and PINs with “helpers” or family members

- Limited understanding of consent when providing information

- Difficulty navigating privacy settings or security features

Without adequate digital literacy, farmers become passive participants in their own data stories rather than active managers of their digital identities.

Balancing Transparency and Privacy

Need for public accountability in welfare schemes

Government welfare schemes aren’t just about throwing money at problems. They’re about making real change in people’s lives. But how do we know if they’re actually working?

This is where public accountability comes in. When the PM Kisan scheme delivers financial support to millions of farmers, taxpayers have a right to know: Is the money reaching the right people? Are there ghost beneficiaries? Is the implementation effective?

Without transparency, welfare programs can become black holes where funds disappear without trace. Open access to beneficiary data helps citizens track whether public money is being spent as intended.

But there’s a catch. True accountability isn’t just about dumping raw data online. It requires:

- Accessible formats that ordinary people can understand

- Regular audits by independent agencies

- Grievance redressal mechanisms

- Citizen monitoring tools

When done right, public accountability creates a virtuous cycle: better implementation leads to improved outcomes, which builds public trust, which in turn strengthens support for welfare programs.

Benefits of open government data

Open government data isn’t just some boring bureaucratic concept. It’s actually revolutionary.

When the government shares PM Kisan data (appropriately anonymized), amazing things happen:

First, researchers can analyze the program’s effectiveness. Are subsidies reaching the poorest farmers? Are women farmers getting equal access? Data tells these stories.

Second, innovators build tools around this data. Think apps that help farmers check their benefit status or NGOs creating maps of coverage gaps.

Third, journalists and watchdogs spot red flags. Unusual patterns in disbursement might signal corruption or implementation problems.

Fourth, other government departments can use this data to improve their own programs. Why reinvent the wheel?

Last but crucial: citizens start trusting their government more. When you can see where the money goes, you’re more likely to believe the system works.

Countries that embrace open data see measurable improvements in service delivery, reduced corruption, and more efficient resource allocation. That’s not just good governance—it’s smart politics.

Privacy-preserving transparency mechanisms

The PM Kisan data dilemma isn’t an either/or situation. We can have both transparency AND privacy. Here’s how:

Data anonymization techniques remove personally identifiable information while preserving the analytical value. Instead of publishing “Rajesh Kumar from Pune received ₹2,000,” systems can share “A farmer in Maharashtra’s western region received the standard disbursement.”

Aggregate reporting provides statistical insights without exposing individuals. Dashboards can show disbursement patterns by district, farm size, or demographic group.

Tiered access systems give different levels of detail to different users. Researchers with proper credentials might access more granular data than the general public.

Federated databases keep sensitive information local while sharing only necessary details with central systems.

Differential privacy adds mathematical noise to datasets in ways that protect individuals while maintaining statistical accuracy.

Consent-based disclosure gives farmers control over their information. A simple opt-in/opt-out system respects farmer autonomy.

These approaches aren’t theoretical—they’re being implemented successfully in welfare programs worldwide. The technology exists. What’s needed is the will to implement it.

Ethical considerations in publishing beneficiary details

The PM Kisan beneficiary list raises thorny ethical questions that go beyond legal compliance.

First, there’s the power imbalance. Farmers—especially small and marginal ones—often lack the digital literacy to understand how their data might be used. When the government publishes their details, are they truly equipped to deal with the consequences?

Then there’s the context problem. Information that seems harmless in isolation can become dangerous when combined with other data. A farmer’s name, land records, and bank details together create a profile that could enable fraud, targeted harassment, or predatory marketing.

We must also consider unintended consequences. When beneficiary lists become public, social stigma might prevent eligible farmers from applying. In areas with social tensions, identifying recipients from certain communities could make them targets.

Digital permanence complicates matters further. Once information is online, it’s practically impossible to truly delete it.

The ethical approach requires asking:

- Does publication serve the public interest or mere curiosity?

- Have beneficiaries been informed about how their data will be used?

- Are the privacy risks proportional to the transparency benefits?

- Who profits from this information, and at whose expense?

Ultimately, respect for human dignity must guide these decisions. Transparency that dehumanizes beneficiaries defeats the purpose of welfare itself.

Future of Data Management in Welfare Schemes

Blockchain and decentralized solutions

The PM Kisan scheme’s data management issues aren’t just a problem—they’re an opportunity for innovation. Blockchain technology could transform how we handle sensitive farmer information.

With blockchain, every transaction gets recorded in a tamper-proof digital ledger. No more mysterious database changes or unauthorized access. Farmers would have a cryptographic key to their own data, giving them control over who sees what.

Several state governments are already running blockchain pilots for land records. Imagine extending this to welfare schemes—each subsidy payment transparently recorded while keeping personal details secure.

The beauty? No single authority controls the entire database. The data exists across thousands of computers, making large-scale breaches nearly impossible.

Anonymization techniques for public databases

The beneficiary lists don’t need to disappear completely—they just need a makeover.

Modern anonymization goes way beyond just removing names. Techniques like differential privacy (used by Apple and Google) add calculated “noise” to datasets while preserving their statistical value.

K-anonymity ensures that each person’s data is indistinguishable from at least k-1 other individuals. With proper implementation, the government could still publish beneficiary information for transparency while protecting individual farmers.

Some practical applications:

- Replacing exact locations with district-level data

- Publishing age ranges instead of birth dates

- Using income brackets rather than exact payment amounts

Consent-based data sharing frameworks

The future of welfare schemes must include giving farmers a say in how their data gets used.

India’s Data Protection Bill (whenever it finally passes) will likely require explicit consent for data processing. But we shouldn’t wait for legislation to implement better practices.

A tiered consent model could work wonders:

- Basic tier: Essential information for payment processing only

- Transparency tier: Anonymized data for public accountability

- Research tier: Data shared with agricultural researchers to improve farming practices

Digital consent management platforms could let farmers update their preferences through simple SMS interfaces or at local kiosks.

Secure authentication technologies

The password is dead—or at least, it should be for accessing sensitive welfare data.

Multi-factor authentication should be standard for everyone accessing the PM Kisan database, from ministry officials to local administrators. This doesn’t have to be complicated either.

Biometric verification through Aadhaar provides one solution, though it needs proper security safeguards. For farmers checking their status, simple SMS-based one-time passwords work well in areas with limited internet.

Zero-knowledge proofs represent the cutting edge—allowing verification without revealing actual data. A farmer could prove they’re eligible without exposing their land records or income details.

Role of digital literacy programs

All these fancy technologies mean nothing if farmers don’t understand how to protect their information.

Digital literacy isn’t a luxury—it’s essential infrastructure. Programs teaching data privacy basics should be integrated into existing agricultural extension services.

Village-level workshops could cover:

- How to check if personal information is being misused

- Understanding which government entities have legitimate access to their data

- Simple security practices like PIN protection on mobile phones

- Rights under existing and upcoming data protection laws

The technical solutions exist. The real challenge is building a culture of data privacy awareness from the ground up.

FAQ’s

Is the PM Kisan beneficiary list publicly accessible?

No, the complete beneficiary list isn’t publicly available to everyone. The government maintains privacy controls that allow farmers to check only their own status through the official portal. You’ll need to enter your registration number or Aadhaar details to view your personal information. This approach balances transparency (so you know where your benefits stand) with privacy protection (so your information isn’t available to just anyone browsing the internet).

How can I check my PM Kisan beneficiary status?

You can check your status in several ways:

- Visit the official website (pmkisan.gov.in)

- Enter your Aadhaar number or registration ID

- Use the PM Kisan mobile app

- Call the helpline at 155261

- Visit your local Common Service Center (CSC)

The fastest method is the website or app, where you’ll get instant confirmation about whether your payments have been processed.

What personal information is collected under PM Kisan?

The scheme collects quite a bit of your personal data:

- Full name

- Aadhaar number

- Mobile number

- Bank account details

- Land ownership records

- Address

- Family information

This information helps verify eligibility and process payments, but it also creates a comprehensive digital profile of millions of farmers across India.

Can my PM Kisan data be used for other government programs?

Yes. The government can use your PM Kisan data for other welfare schemes or agricultural programs. While this integration can streamline access to multiple benefits without requiring you to submit the same documents repeatedly, it also means your information flows between different government databases. The government calls this “data sharing for public good,” but critics worry about the lack of clear consent mechanisms for these secondary uses.

What happens if I find incorrect information in my PM Kisan profile?

Found a mistake? Contact your local agriculture officer or visit the nearest PM Kisan Seva Kendra immediately. Errors in your profile could delay or prevent your benefit payments. The correction process typically requires supporting documents and might take a few weeks to update in the system.

Safeguarding Farmer Privacy in the Digital Age

The PM Kisan Scheme represents a significant step toward financial support for India’s farming community, but it also highlights the delicate balance between transparency in government programs and protecting individual privacy. As we’ve explored, the beneficiary list reveals both the scheme’s impressive reach and concerning vulnerabilities in data protection practices. With existing legal frameworks struggling to keep pace with digital transformation, farmers face real consequences when their personal information isn’t properly secured. The push for transparency in welfare distribution must be counterbalanced with robust privacy safeguards that protect those the program aims to serve.

Moving forward, the future of welfare scheme data management requires a proactive approach. Government agencies must implement stronger encryption, clearer consent mechanisms, and better control over how beneficiary information is shared and accessed. For farmers concerned about their data, staying informed about privacy rights and regularly verifying their information accuracy are essential steps. By addressing these challenges now, India can create a model that delivers welfare benefits efficiently while respecting and protecting the privacy dignity of its agricultural communities.